Bertrand Russell and the “unsolved“ philosophical problem of consciousness. Below excerpt Russell’s theory of Philosophy of Mind (Neutral Monism) — broadly speaking, the view consciousness is intrinsic to matter, that the brain and mind physically the same. The upshot of this is neutral monism provides a possible solution to what is currently understood as “the hard problem of consciousness“.

“I maintain an opinion which many other philosophers find shocking: namely, that people’s thoughts are only in their heads. What I maintain is that the occurrence in the brain is a visual sensation. I maintain, in fact, that the brain consists of thoughts — using ‚thought‘ in its very widest sense, as it is used by philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650). To this people will reply ‚Nonsense! I can see a brain through a microscope, and I can see that it does not consist of thoughts but of matter just as tables and chairs do.‘ This is a sheer mistake.

What you see when you look at a brain through a microscope is part of your private world. It is the effect in you of a long causal process starting from the brain that you say you are looking at. The brain that you say you are looking at is, no doubt, part of the physical world; but this is not the brain which is a datum in your experience. That brain is a remote effect of the physical brain. And, if the location of events in physical space-time is to be effected, as I maintain, by causal relations, then your percept, which comes after events in the eye and optic nerve leading into the brain, must be located in your brain.

We can approach the same result by another route. When we were considering the photographic plate which photographs a portion of the starry heavens, we saw that this involves a great multiplicity of occurrences at the photographic plate: namely, at the very least, one for each object that it can photograph.

I infer that, in every small region of space-time, there is an immense multiplicity of overlapping events each connected by a causal line to an origin at some earlier time — though, usually, at a very slightly earlier time. A sensitive instrument, such as a photographic plate, placed anywhere, may be said in a sense to ‘perceive‘ the various stars and distant galaxies from which these causal lines emanate. We do not use the word ‚perceive‘ unless the instrument in question is a living brain, but that is because those regions which are inhabited by living brains have certain peculiar relations among the events occurring there.

The most important of these is memory. Wherever these peculiar relations exist, we say that there is a percipient. We may define a ‚mind‘ as a collection of events connected with each other by memory-chains backwards andforwards. We know about one such collection of events — namely, that constituting ourself — more intimately and directly than we know about anything else in the world. In regard to what happens to ourself, we know not only abstract logical structure, but also qualities — by which I mean what characterizes sounds as opposed to colours, or red as opposed to green. This is the sort of thing that we cannot know where the physical world is concerned. There are three key points in the above theory. The first is that the entities that occur in mathematical physics are not part of ‚the stuff of the world‘, but are constructions composed of events and taken as units for the convenience of the mathematician. The second is that the whole of what we perceive without inference belongs to our private world.

The starry heaven that we know in visual sensation is inside us. The external starry heaven that we believe in is inferred. The third point is that the causal lines which enable us to be aware of a diversity of objects, though there are some such lines everywhere, are apt to peter out like rivers in the sand. That is why we do not at all times perceive everything. I do not pretend that the above theory can be proved. What I contend is that, like the theories of physics, it cannot be disproved, and gives an answer to many problems which older theorists have found puzzling. I do not think that any prudent philosopher will claim more than this for any mind theory.“

—

Bertrand Russell, My Philosophical Development (1959), Ch. II: My Present View of the World,

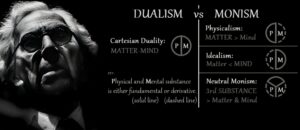

Background: Russell’s theory of Mind Philosophy (Neutral Monism)

Russell was a neutral monist coining the term itself. Neutral monism is an umbrella term for a class of metaphysical theories in the philosophy of mind. These theories reject the dichotomy of mind and matter, believing the fundamental nature of reality to be neither mental nor physical; in other words it is “neutral“. Russell was attracted to neutral monism due to its parsimony (Ockham’s razor is a philosophical principle which can be used to decide to prefer one explanation of a phenomenon over another. It is also known as the principle of parsimony or the law of parsimony).

Neutral monism is similar to dualism in that both take reality to have both mental and physical properties irreducible to one another. Unlike dualism however, neutral monism does not take these properties to be fundamental or separate from one another in any meaningful sense. Dualism takes the mind to supervene on matter, or – though this is less common – for matter to supervene on the mind.

Neutral monism, in contrast, take both mind and matter to supervene on a neutral third substance. Philosopher David Chalmers, an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist specializing in the areas of the philosophy of mind, has been known to express sympathy toward neutral monism. In The Conscious Mind (1996) he concludes that facts about consciousness are “further facts about our world“ and that there ought to be more to reality than just the physical. However, he then goes on to engage with a Platonic rendition of neutral monism that holds information as fundamental. Despite Russell’s well reasoned arguments, neutral monism has not been a popular view in mind philosophy as it is difficult to develop or understand the nature of the neutral elements.

Image left: Bertrand Russell, 1954. Image right: A diagram showing the relationship between neutral monism and three other philosophical theories. Elements within the solid lines are fundamental, whereas elements within the dotted lines are non-fundamental.

Celá debata | RSS tejto debaty